It is easy to get caught up in the thrill of new trends that seem to be the solution to all our problems. This is especially the case for Pay For Success (PFS) contracts. They not only provide an infusion of private dollars in the face of shrinking government budgets, but, in theory, they also enable successful programs to rapidly scale beyond the capacity of most nonprofits’ fundraising capabilities. While the promise of PFS hasn’t been completely squashed, the closure of New York City’s Rikers Island and England’s Petersborough PFS contracts earlier this year are perhaps a cautionary tale for communities considering a ride on the bandwagon. Here are just a few of the key takeaways from these projects to keep in mind before making a PFS commitment in your community.

The PFS project at Rikers Island entailed scaling cognitive behavioral therapy to youth detained at the facility. The team at Rikers Island was set up for scaling success:

- Cognitive behavior therapy is an evidence-based intervention that has been successful in reducing youth recidivism nationally.

- The service providers, Friends of the Island Academy and Osbourne Association, have 110+ years of combined experience working with this population.

- The providers were experienced in administering this form of therapy.

- The project was fully funded at $7.2 million.

On paper, the providers were supposed to succeed in reducing recidivism by 10 percent over a three-year period, but they didn’t. This underscores the complexity and unpredictability of social interventions and just how tough scaling can be.

PFS is not cheap

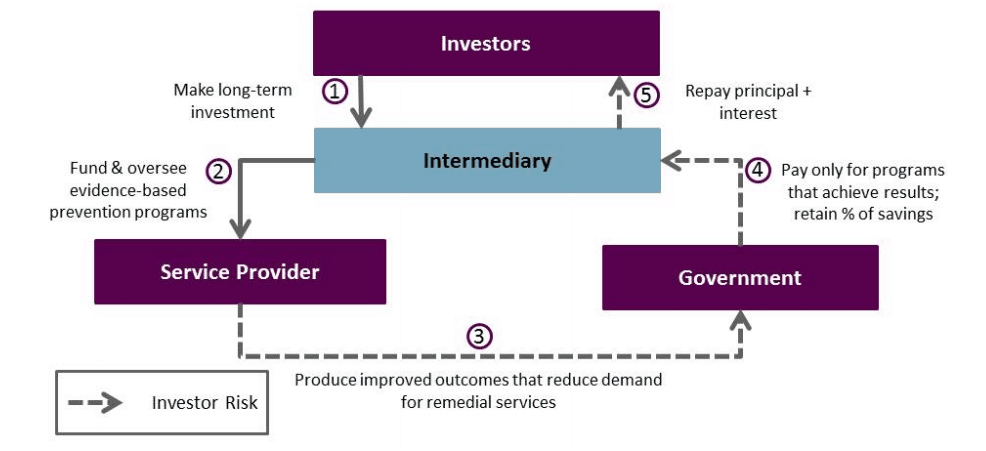

An allure of PFS is that the government does not pay unless the service providers hit predefined goals. But, anticipated payouts can scare the government away from investing in PFS projects or seeing them through. While the recidivism project in Petersborough was on track to meet targets, the British government called for an early phase-out of the contract. Reports speculate that the government may have been trying to save money by contracting directly with service providers, thereby cutting out costly intermediaries (i.e., returns to investors and evaluators). Additionally, the true cost of PFS projects (and savings to taxpayers) can be hard to calculate. Reports about PFS projects in the U.S. emphasize that while the government is not yet paying, a significant amount of public time has already been donated to make these projects work.

PFS is still unproven

Each year, the number of communities in the U.S. launching PFS feasibility studies and contracts increases. But, PFS as an investment tool and social problem-solver is still being evaluated. For example, the shutdown of the Rikers Island and Petersborough projects isn’t all bad news. By all accounts, these projects had been functioning in the way PFS creators intended. Despite their outcomes, this fact is a win for PFS and the social sector. However, many aspects of PFS can affect project outcomes, including the issues the projects address. Recidivism is not the only focus of the 20+ PFS projects currently in the works – universal pre-K, homelessness, and child and maternal health are also among the issues being tested. Success in alleviating these varied social problems through PFS remains to be seen. Given that we have not yet seen a PFS contract that was a clear homerun, organizations should still proceed with caution before making the significant investment of time and resources in PFS.

Pay For Success is anyone’s game right now. It may work for some social issues and not for others; only time will tell which conditions make it optimal for success. If you are one of our Social TrendSpotters working on PFS contracts in your community, please chime in on this post-mortem of the Petersborough and Rikers Island projects. We would love to hear your perspective and analysis.

Research clearly shows that the single most important aspect of behavioral change is Client Engagement. That means Client

Self Motivation, Client Support System Motivation, and the Helper Relationship with the Client. As a Clinical Counselor and Counselor Educator, the particular type of intervention, such as Cognitive Tx, is relatively unimportant compared to Motivation and Relationships.

This is disappointing, particularly if the project was indeed tracking to meet objectives before the premature cancellation. I wish we could get an in-depth case study on this project to determine:

1) Did the nonprofit partners have a delayed start for some reason?

2) Was there an issue with ramping up the personnel on time (i.e. these jobs obviously require very particular talents and personality traits, and it can be hard to recruit a large number of such positions at one time while maintaining standards of quality)?

3) Were there unforeseen participation challenges on the part of the clients — i.e. slow referral pipeline from the administration, burdensome intake process that resulted in many clients getting off on the wrong foot? And what about the likely challenge of scaling an intervention that potentially relied on one-on-one engagement/small group engagement; if they had to dramatically increase the student-to-staff ratio or increase the average class size, the could have negatively impact results.

Of course, all of these challenges should have been anticipated. I hope that the poor results of this high-profile PFS project do not take away from the credibility of the concept overall. Many organizations here in Texas (Prison Entrepreneurship Program, Youth With Faces, etc.) are delivering phenomenal results that would be strongly aligned with a PFS funding model. I would hope that states can look past the failures of this one experiment and see the opportunities that PFS presents for expanding the impact of proven models.

(On that last note, I wonder if part of the challenge is the use of the word “scaling” … social initiatives face many hurdles that technology initiatives do not, and scaling is not simply a matter of adding users but also expanding core infrastructure)