We spend a lot of time as a team discussing the differences between trends and fads within the social sector. Impact investing falls in a gray area – where we still have so much to prove, yet we need it to work in order to have financial resources to solve some of our most vexing social problems. Our friend and fellow TrendSpotter, William Burckart, is one of our go-to experts on this topic. In his piece below, originally published in The Chronicle of Philanthropy, he discusses the need for progress in the realm of impact investing and what needs to happen for it to be a real force for change. He also did a great interview with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and longer report on the topic. We welcome your feedback on this important topic and will continue to update you as the issue evolves.

We spend a lot of time as a team discussing the differences between trends and fads within the social sector. Impact investing falls in a gray area – where we still have so much to prove, yet we need it to work in order to have financial resources to solve some of our most vexing social problems. Our friend and fellow TrendSpotter, William Burckart, is one of our go-to experts on this topic. In his piece below, originally published in The Chronicle of Philanthropy, he discusses the need for progress in the realm of impact investing and what needs to happen for it to be a real force for change. He also did a great interview with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and longer report on the topic. We welcome your feedback on this important topic and will continue to update you as the issue evolves.

“I’d heard Egypt was doing really well according to all the metrics that we pay attention to at the World Bank,” said Aleem Walji of the World Bank Institute at a Federal Reserve conference in 2011.

“Investment was up, returns were good, we were investing in all the right sectors, or so we thought.”

Then the Arab Spring happened. Clearly, the World Bank’s metrics had not captured the deep frustration of Egyptian youth, who were cut out of the supposedly expanding economy there.

Around the same time, the Latin American Youth Center, a Washington charity, was running a parenting program that included a few new sessions on preventing domestic violence. According to most measures, the center was successful: It was serving more than 4,000 individuals each year.

But when Isaac Castillo, who was then the center’s director of learning and evaluation, reviewed participants’ tests before and after the classes, he realized something had gone terribly wrong. The domestic-violence sessions were changing participants’ attitudes in the wrong direction: More young parents were leaving the program believing that domestic violence was an acceptable expression of love.

These two very different cases highlight the importance of looking beyond the usual metrics — whether they are return on investments or numbers of program participants — to prevent disastrous outcomes. While human beings are complicated, messy, and unpredictable, metrics and systems that are supposed to measure and manage impact are often not dynamic enough to reflect all that human complexity.

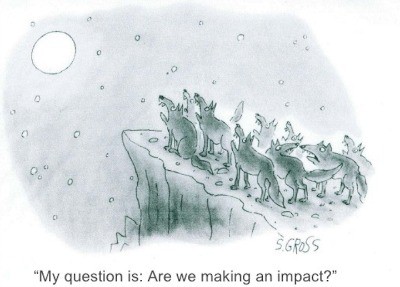

Yet investors, grant makers, and nonprofit organizations need to have some way to assess, manage, and communicate their real impact. This can be especially difficult when the two worlds of investing and philanthropy get mixed together as an impact investment, which is meant to achieve a measurable social or environmental impact alongside a financial return.

In a new report I wrote for the Money Management Institute titled “Bringing Impact Investing Down to Earth: Insights for Making Sense, Managing Outcomes, and Meeting Client Demand,” we argue that it’s time for people interested in impact investing to adopt the ideas nonprofits are using to track progress.

Many of the venture philanthropists who started making grants in the 1990s and early 2000s understood the limitations of simple measures like the number of houses built. They focused instead on what they wanted to achieve, such as helping low-income people achieve the financial stability they needed to stay in those houses for a long time.

Such investors wanted a way of measuring every social program to determine whether it was meeting long-term goals the program was created to address.

This kind of focus on outcomes is what helped the Latin American Youth Center realize that its sessions on domestic violence had backfired. “In a very real sense, our program caused harm to our participants, despite the best of intentions,” Mr. Castillo wrote in the book Leap of Reason.

The nonprofit was able to respond quickly to the problem not only because it had a system in place to track performance but also because everyone at the organization — from the board to the direct service providers — understood the value of collecting and reviewing data about the programs and participants every week.

The changes the youth center made worked, including splitting the classes into separate rooms for men and women so that each could feel more comfortable expressing their feelings.

Impact investments need to be similarly assessed to ensure they are making the social or environmental impact they promise. Making and managing investments that aim to build communities or preserve the environment while still generating a financial return presents a complicated proposition for the financial-services industry. The industry is measuring the financial behavior of an investment while also dipping its toes into the realm of the nonprofit world, where outcomes-centered measurement is still a difficult calculus that’s never fully solved.

There are some tools to help impact investors measure the nonfinancial performance of their investments and even compare investments by the social good they achieve. Among them are sustainability-reporting guidelines like the Global Reporting Initiative; impact and sustainability metrics like the Impact Reporting and Investment Standards; and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board.

There are also ratings and analytical tools like the Global Impact Investing Rating System, B Impact Assessments, B Analytics, and B Corporation certification. But these systems still don’t take into account things like place, organizational performance, or type and timing of capital deployed. Instead, they still focus on numbers, devoid of context.

Neglecting this context leaves the door open for fund managers to slap a few vague metrics on an investment fund just to market it as an impact investment.

For example, an impact fund manager was criticized for a 2014 deal to finance a South African textile importer. Critics said the investment could actually have a negative impact on the local textile industry; that it might not be a good thing for locals, who often purchase clothing on debt; and that there would be a negative environmental impact since importing cheap goods from Asia would result in a larger carbon footprint than producing textiles locally with the ready supply of labor in South Africa. We must learn how to capture the right data to ensure that funds calling themselves “impact investments” are legitimate.

It’s not only good practice for impact investors to measure real outcomes the way nonprofits do — or try to — it’s also an effective and efficient way to solve social problems. Take the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which came under fire in 2007 when the Los Angeles Times exposed that some of the investments the foundation was making on behalf of its endowment were actually causing the very afflictions the foundation had set out to combat as part of its grant making.

Among the concerns: The foundation was funding vaccinations to prevent illnesses affecting people in the Niger Delta while its endowment was invested in companies like Royal Dutch Shell and Exxon Mobil, which were largely responsible for the pollution that was covering the delta and causing poor health in the first place. The foundation has since made moves to align its charitable mission with its endowment investing, something all foundations should consider.

Impact investing has the potential to make an indifferent economy more humane, but only if we come up with a way to measure investments so that we understand their effects on the people, the environments, and the communities they touch.

To move toward that goal, nonprofits and foundations must be open to partnerships with the financial-services industry to share their knowledge and strategies for outcomes measurement. The financial services industry, in turn, must be open to using the tools and firms that nonprofits rely on to evaluate their programs and communicate outcomes.

Impact investing can be a deeply rooted force for social progress. Now all of us can help prove it.

Excellent observations. It is a difficult transition to evaluate endowment outcomes based on metrics a particular group has no experience with or is outside their job mandate. Especially when

Likewise, there are investment alternatives to grants on the program side (program-related investments -PRIs), that can supplement and expand the effectiveness of program capital. These investments require a new focus as well but are outside of the comfort level (experience or expertise-wise) of those on this side of the table.

A willingness to explore new ways of looking at how philanthropic capital can be viewed and utilized is often difficult to implement because change is hard. Looking outside the box in terms of collaborating between financial and program activities will be a big step toward making progress in this area.